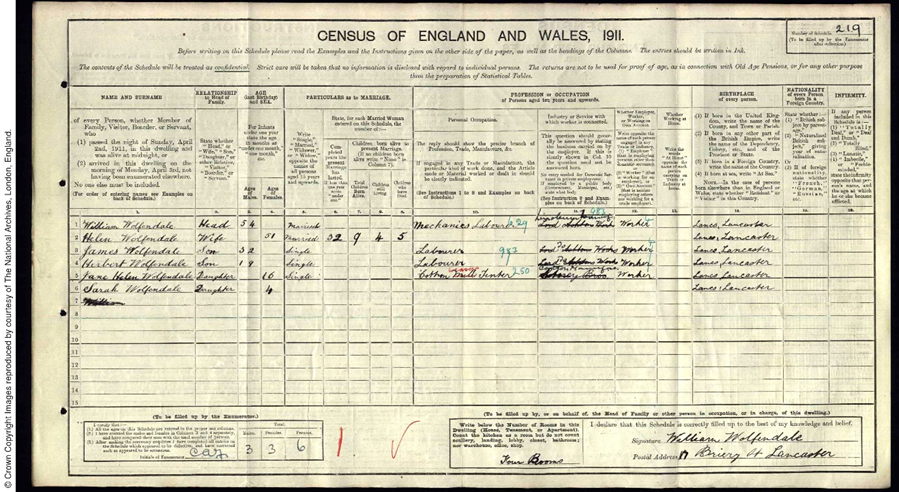

My maternal Grandmother, Mary Ellen Downes, nee Clarkson (1916-2003) was born in Lancaster and her mother’s maiden name was Mary Alice Wolfendale. Mary Alice appears from the Baptism records to have been born in 1888 the 5th child of her parents William and Ellen. On the 1911 census (below), Ellen is required to say how many children she has had in total – she says 9, and how many are still living – she says 4. My investigations confirm to me that 5 did indeed die as babies: James in 1880, Johnathan in 1881, John Henry in 1883, Lily Beatrice in 1897 and Richard in 1899. A very sad infant mortality rate.

Although Victorians who attained adulthood could expect to live into old age, average life expectancy at birth was low: in 1850 it was 40 for men and 42 for women. By 1900 it was 45 for men and 50 for women. The very low life expectancy is skewed by the fact that in the 1850s a quarter of children died before the age of 5. By 1900 it was still 150 per 1000 – ie 15% of all children born alive. By 2021, the infant mortality rate in the United Kingdom was four deaths per 1,000 live births – 0.4%. Thankfully, we now have one of the lowest infant mortality rates in the world.

Despite Ellen stating that she has only 4 living children on the 1911 census, my research indicates that 6 of her children appear to be very much alive in 1911. 4 are on the 1911 census with her and her husband William: James, Herbert, Jane Ellen and Sarah. George, I cannot find in 1911, but in 1921 his parents, William and Ellen, are living with him and his wife and daughter, so he is obviously alive in 1911. And my own Great Grandmother, Mary Alice, William and Ellen’s daughter, is living a couple of doors away from them in 1911, on the same street, with her husband and her sole surviving child, James (Elizabeth Alice having died at 6 weeks old in 1908).

So why the discrepancy? It is very odd. One very real possibility is that Sarah, born at the end of 1906 when Ellen was about to turn 48, and almost 8 years after her nearest sibling, was not in fact their daughter, but their grandaughter. I strongly suspect that Mary Alice, who would have been 18 when Sarah was born, and the only daughter old enough, was actually her mother. And therefore Sarah was my Nan’s half sister.

To try to clarify this, I sent off for Sarah’s actual birth certificate, and this does record William and Ellen as parents. However my research suggests that it was not uncommon for grandparents to bring up their illegitimate grandchildren as their own, and even to have registered the birth. There simply weren’t background checks then which would have caught people out. I have noticed similar large gaps on other family trees between the penultimate sibling and the “baby” of the family, where at least one of the “sisters” is already an adult. And in view of the historic stigma associated with illegitimacy, it wouldn’t surprise me if the youngest child of the family, was in fact, a grandchild.

As a postscript to my story, I know that my Nan always said that her father’s family felt he had married beneath him, and this despite his ancestry being, on paper, every bit as working class as Mary Alice Wolfendale’s family. Perhaps it was the stigma of illegitimacy affecting their views.

In 2021, more babies – 51% – were born to unmarried mothers in England and Wales than to those in a marriage or civil partnership, for the first time since records began in 1845. This is a huge change. For centuries, “illegitimacy” and unmarried parenthood has been associated with stigma, shame and disadvantage.

There is good evidence that at least a third, if not possibly a half, of brides in the 1800s would have been pregnant on their wedding day. Where I am able to determine the exact wedding day because there are Parish records, and also the date of birth of the first baby, then I would estimate from my research, that 50% of brides I have traced for the purposes of a family tree, were pregnant on their wedding day.

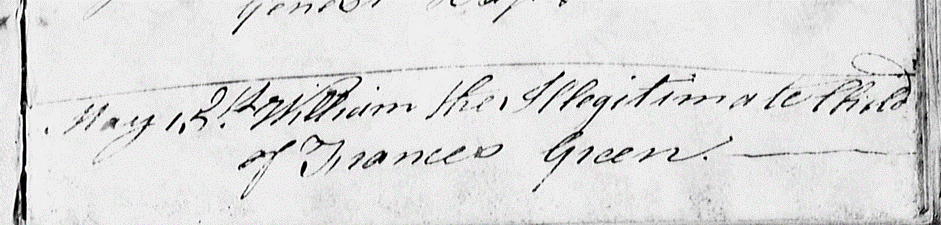

Such was the stigma of illegitimacy that for a long time it was specifically noted in the Parish records. Thus here is a Lincolnshire entry I came across from 1758.

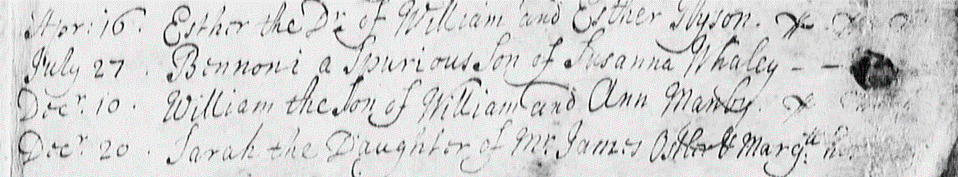

Back in 1699 the illegitimate child was referred to as “spurious”. See below.

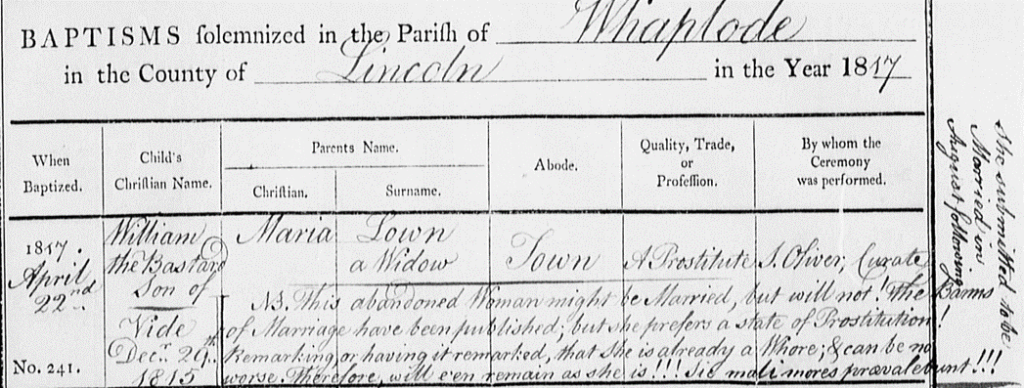

Further back, the child would simply have been called “bastard son of…” in the Parish register. But as recently as 1817, the horrified Curate “S. Oliver” of one Lincolnshire Parish, not only recorded the child as “William the Bastard son of Maria Lown”, but also describes the mother’s trade as “A Prostitute”. He then appears to resort to Latin to really have a go at her – and my poor memory of O Level Latin prevents me from translating! Maybe that’s a good thing!

Unmarried mothers continued to experience the stigma associated with illegitimacy well into the 20th century. They found it difficult to get work, and enforce maintenance payments for their children until quite recently, relatively speaking. Before 1977, for example, unmarried mothers and their children were usually excluded from council housing lists. It was only in 1987 that the legal distinction between legitimate and illegitimate was finally eradicated.

At last as a society we now appear to be largely free of any perception that the marital status of a person’s parents is relevant to their standing in the world. And thank goodness for that!

Now I am not finished with Sarah Wolfendale. At some point in the future I will return to her story, and explain how “stigma and shame” relating to other issues, had a massive impact on her life…